Scientists suggest that the ability to detect sarcasm, often considered the lowest form of wit, could assist AI in interacting with people more naturally

Despite being capable of passing the bar exam, excelling in medical tests, and reading bedtime stories with emotion, artificial intelligence will never truly rival the marvel of the human mind until it masters the art of sarcasm.

However, this mastery may be the next feat on the technology’s impressive list of capabilities. Researchers in the Netherlands have developed an AI-driven sarcasm detector that can identify when sarcasm, often considered the lowest form of wit and the highest form of intelligence, is being used.

“We can reliably recognize sarcasm and are enthusiastic about expanding on that,” stated Matt Coler from the University of Groningen’s speech technology lab. “We want to explore the extent to which we can advance this capability.”

The project entails more than just instructing algorithms that occasionally even the most enthusiastic remarks should not be taken literally but rather as their exact opposite. Coler mentioned that sarcasm pervades our conversations more than we might realize, so comprehending it is vital for seamless communication between humans and machines.

“When you begin studying sarcasm, you become acutely aware of how extensively we use it in our everyday communication,” Coler explained. “However, we have to communicate with our devices in an extremely literal manner, as if we’re addressing a robot, which is essentially what we’re doing. But it doesn’t have to be this way.”

Humans are generally skilled at recognizing sarcasm, although it is more challenging in text alone compared to face-to-face interactions where delivery, tone, and facial expressions indicate the speaker’s intent. In developing their AI, the researchers discovered that multiple cues were also important for the algorithm to differentiate between sarcastic and sincere statements.

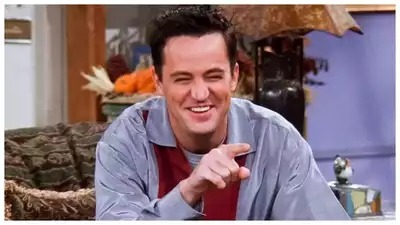

During a presentation at a joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the Canadian Acoustical Association in Ottawa, Xiyuan Gao, a PhD student at the lab, discussed the group’s work. They trained a neural network using text, audio, and emotional content from video clips of US sitcoms such as Friends and The Big Bang Theory. The database, named Mustard, was created by researchers in the US and Singapore. They annotated sentences from the TV shows with sarcasm labels to develop their own sarcasm detector.

The AI was trained on various scenes, including one from The Big Bang Theory where Leonard tries unsuccessfully to escape from a locked room, leading Sheldon to remark, “It’s just a privilege to watch your mind at work.” Another scene from Friends involves Ross inviting Rachel to join Joey and Chandler in assembling furniture, prompting Chandler to sarcastically comment, “Yes, and we’re very excited about it.”

Following training on text and audio, along with emotional content scores derived from actors’ dialogue, the AI could detect sarcasm in unlabelled exchanges from the sitcoms with an accuracy of nearly 75%. Additional research at the lab has leveraged synthetic data to enhance accuracy further, but this work is pending publication.

Shekhar Nayak, another researcher involved in the project, suggested that besides enhancing interactions with AI assistants, the same approach could be applied to identify negative language and detect instances of abuse and hate speech.

Gao mentioned that further enhancements could involve incorporating visual cues into the AI’s training data, such as eyebrow movements and smirks. This raises the question of what level of accuracy is sufficient. “Are we aiming for a machine that is 100% accurate?” Gao pondered. “That’s a level even humans can’t consistently achieve.”

Coler adds that making programs more attuned to how people truly speak should facilitate more natural conversations with devices. However, he wonders about the implications if machines begin to use sarcasm themselves. “If I ask, ‘Do you have time for a question?’ And it responds, ‘Yeah, sure,’ I might be unsure if it actually does.”